Insights

Challenging Stereotypes: Changing the Narrative Around Who Is “Good at Math”

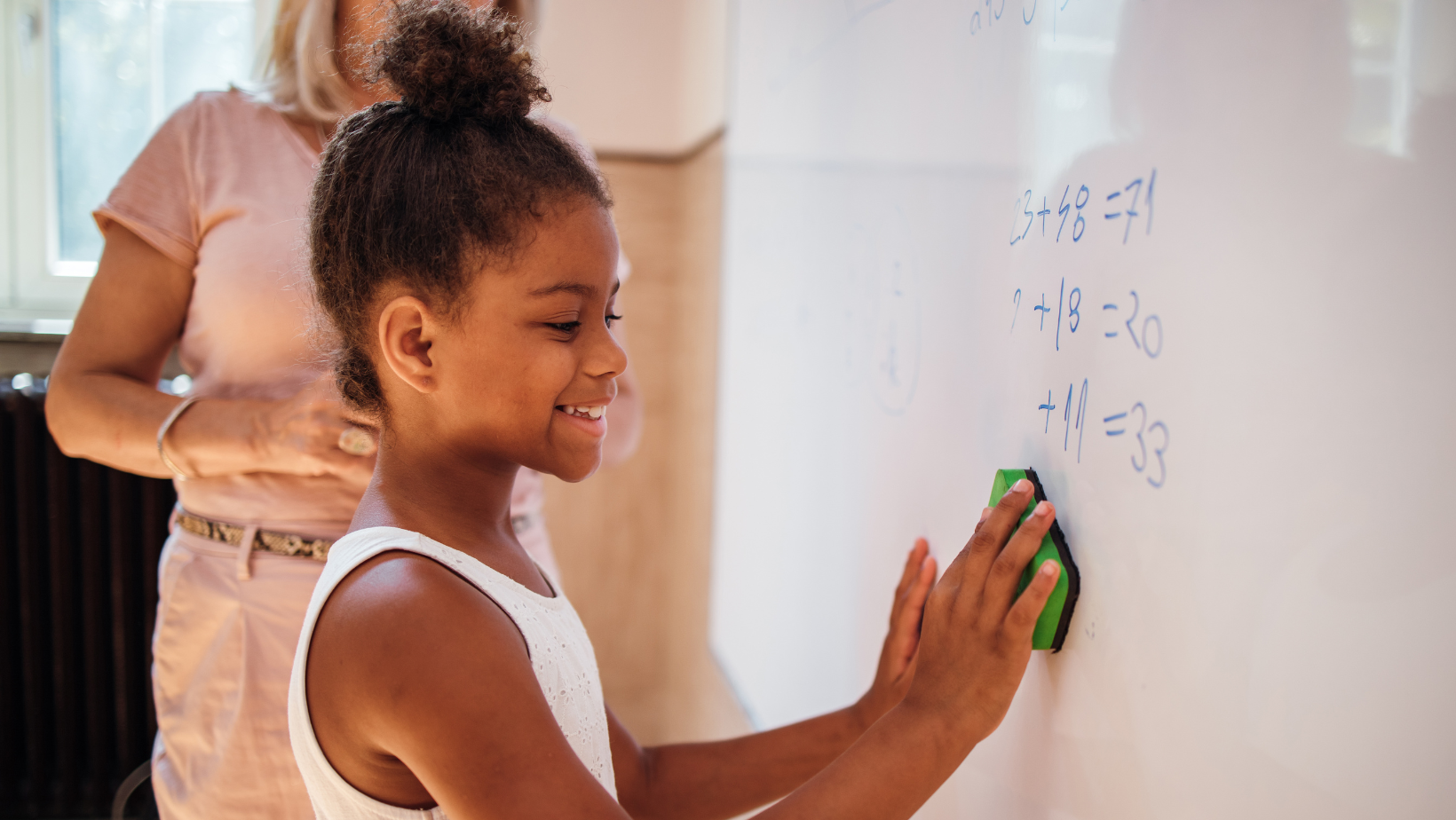

For many years, students have absorbed a quiet message about math—sometimes from the media, sometimes from adults, and sometimes from the classroom itself. That message is that only certain kids are “math people.” Maybe they’re fast with facts, maybe they raise their hands first, or maybe they complete their work neatly and quietly. But as educators, we know the truth: mathematical thinking shows up in far more diverse and creative ways than our students have been taught to believe.

Challenging stereotypes around math ability is not just a mindset shift—it’s instructional work. It requires us to rethink how we talk about math, what kinds of tasks we offer, and how we value the variety of strategies students bring to the table. When children see themselves as capable mathematicians, everything changes: participation increases, confidence grows, and achievement follows.

Below are research-backed practices and classroom strategies for building a math community where all students can thrive.

Why Math Stereotypes Persist in Elementary Classrooms

Stereotypes about who is “good at math” tend to center on speed, accuracy, and getting the “right” answer quickly. But decades of research (including studies from Stanford math-education researcher Jo Boaler and growth-mindset psychologist Carol Dweck) show that mathematical success is actually driven by flexible thinking, perseverance, collaboration, and the ability to explain reasoning—not speed.

Still, these misconceptions persist because:

- Timed tests and fast-fact culture reinforce the idea that speed = intelligence.

- Students compare themselves constantly—even as early as kindergarten.

- The media often portrays “math people” as naturally gifted rather than hard-working.

- Adults sometimes unintentionally say things like “I’m just not a math person,” sending a message that math ability is fixed.

A key part of our work is helping students learn a different story—one where math is creative, visual, logical, and accessible to every learner.

Shift the Focus From Speed to Mathematical Thinking

One of the most powerful ways to break stereotypes is to move the focus from fast answers to thoughtful strategies. Instead of praising students for being “quick,” we can praise them for being thorough, clever, or persistent.

What this looks like in the classroom

- Encourage students to explain how they solved a problem, not just what they got.

- Highlight multiple correct solution paths and celebrate differences.

- Offer low-floor, high-ceiling tasks so all students can enter and extend thinking.

How ORIGO supports this shift

Resources like Think Tanks align beautifully with this mindset. Each activity offers rich problem-solving experiences that naturally invite diverse strategies. Students explore, discuss, and explain, showing that mathematical thinking—not speed—is the goal.

Stepping Stones 2.0 also integrates visual, verbal, and symbolic models that support conceptual understanding before formal procedures. This structure helps all learners, not just those who move quickly.

Highlight the Many Identities of Mathematicians

We can broaden students’ understanding of what a mathematician looks like and does.

Classroom moves that make a difference

- Share stories of mathematicians from a variety of backgrounds. Give these a try!

- Use math read-alouds that show problem solving through collaboration and creativity.

- Showcase student thinking on bulletin boards—not just perfect work, but unique strategies, sketches, and models.

ORIGO’s Big Books and Animated Big Books immerse students in rich math stories where characters problem-solve in fun, visual ways. These stories help children see math as something they do, not something certain people are born with.

Normalize Mistakes in Math as Part of Learning

If students believe that “good” math learners never make mistakes, they quickly assume that errors signal a lack of ability. But research shows the opposite: mistakes strengthen neural pathways and deepen understanding.

Ways to build a mistake-friendly math culture

- Publicly model mistakes and show how you work through them.

- Use phrases like “Thank you for giving us something important to think about.”

- Include error-analysis tasks where students identify, correct, and explain thinking.

ORIGO resources that make this easier

ORIGO’s Fundamentals are games that offer opportunities to practice strategies and give feedback on each other’s work in a fun context. These games help students test ideas, revise thinking, and try again without fear.

Provide Tasks That Allow Every Student to Shine

Stereotypes break down fastest when students regularly succeed in multiple ways. Providing tasks that emphasize reasoning, patterning, spatial problem-solving, or hands-on modeling gives students varied access points. And as 5 Practices for Orchestrating Productive Mathematics Discussions (Second Edition) by Margaret Smith and Mary Kay Stein reminds us, the way we structure student sharing matters.

When sharing student work, deliberately sequence the order in which students share their thinking so everyone has a chance to contribute and see one another’s thinking. If the “perfect answer” is always shared first — by the student who raises their hand first — others lose the opportunity to be heard.

Classroom examples

- Pattern-building tasks where students predict and extend sequences

- Geometry explorations with manipulatives

- Real-world problems with multiple correct outcomes

- Collaborative puzzles and games

ORIGO’s Number Cases give students concrete tools for modeling addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. These hands-on experiences help students who may struggle with symbolic-only tasks shine through visual reasoning.

ORIGO’s Mathementals (daily review routines) also reinforce foundational ideas through short, meaningful practice—helping students grow confidence in manageable steps.

Strengthen Student Voice and Agency

Students often internalize math stereotypes because they feel math is something done to them, not by them. When students reflect on growth, set goals, and recognize strengths, they begin to see themselves as mathematical thinkers.

Practical strategies

- Let students choose which strategy they want to share.

- Have them reflect weekly on “something in math I’m proud of…”

- Ask students to name what helped them solve a problem (tools, drawings, teamwork, etc.).

The built-in structure of Stepping Stones 2.0 Student Journals encourages students to record and explain thinking. Over time, they see evidence of their own mathematical growth—one of the strongest antidotes to harmful stereotypes.

Promote Collaboration Over Competition in Math

Competition often reinforces stereotypes by rewarding students who finish quickly and quietly. Collaborative problem solving, however, highlights a diversity of strengths.

Classroom practices

- Pair students strategically so different strengths surface together.

- Use group tasks that require multiple roles—explainer, checker, modeler, recorder.

- Celebrate collective strategies as much as individual ones.

ORIGO’s Think Tanks and Stepping Stones’ exploratory lessons give students natural opportunities for collaborative reasoning. These open-ended tasks show students that strong math communities are built on teamwork, not competition.

Creating a Math Culture Where Every Child Is a Math Child

When we actively challenge stereotypes about who is “good at math,” we give students a gift that lasts far beyond elementary school—a sense of agency, curiosity, and confidence.

Math becomes a subject where all strategies matter, mistakes are part of progress, identity grows with effort, and every learner can shine.

With intentional classroom culture, diverse tasks, and supportive resources like those from ORIGO Education, we can ensure that every student sees themselves as a capable, creative mathematician.